|

||||||

|

| ||||||

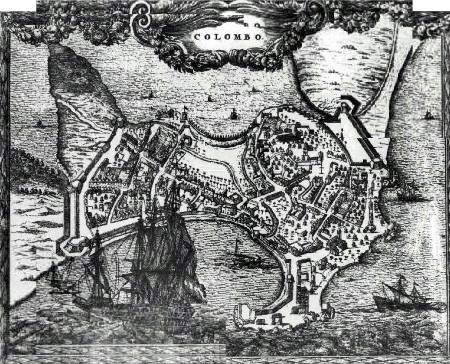

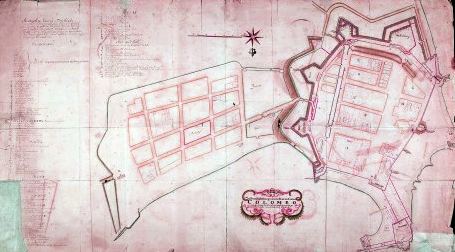

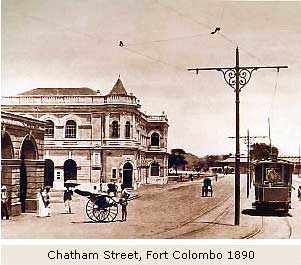

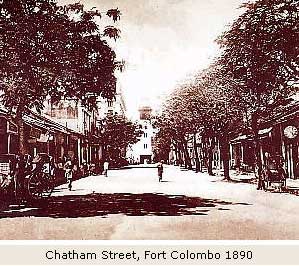

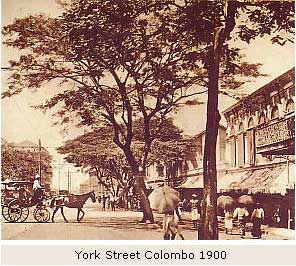

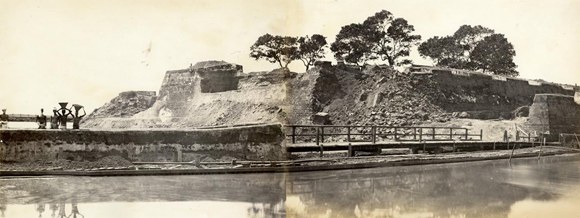

Historic Colombo Fort Demolition of the Dutch Fort, Colombo c.1865 Fort, between Colombo Harbour to the north and Beira Lake to the south, is the heart of Colombo. The Portuguese built and extended their fortress here during more than a century of conquest and resistance. It was taken over by the Dutch, and finally demolished by the British after they completed their conquest of the country in the mid-19th century. Today, the area is the city's financial and commercial heart and houses Colombo's main international hotels, as well as Sri Lanka's seat of government. The mid-19th-century Clock Tower, at the comer of Janadhipati Mawatha and Chatham Street, was originally a lighthouse and is now a handy landmark for the city centre area. Other landmarks include the President's House and Presidential Gardens, a palatial neo- classical building which was originally the home of the British Governors and is now the residence of Sri Lanka's president; it is sadly off limits to visitors. The business district of Colombo, with Government buildings, banks and other commercial ventures, five-star hotels and department stores, is still called 'Fort', because that is what it once was. The Fort of Colombo, which like Jaffna and Galle was really a fortified town, was demolished around 1870 in the interest of urban development, soon followed by most of the buildings within it. Today nothing is left but its shape in aerial photographs, the regular grid pattern of the streets, some parts of the walls, the hospital, the lonely Delft Gate that is now a useless passageway hidden among modern high-rise, hardly recognizable parts of the Governor's House, and some odds and ends, like an ugly and lost little warehouse in the harbour. Of course today the historical remains are more appreciated, as monuments to history and sites of tourist interest, so most of the buildings that do remain have recently been renovated. The most important ones are located outside the original Fort area, such as the Dutch Period Museum and the Wolfendhal Church. After taking the Portuguese fort of Colombo in 1656, the Dutch partially demolished it, and restructured and improved the western part, taking advantage of the natural strength of the location between a lake and the sea. On the landside there was a wide moat connected to the lake which was infested with crocodiles, and beyond that the Pettah arose, the 'old city'. The old Portuguese walls and bastions were demolished there. The Fort was connected with the Pettah via Koningsstraat, now Main Street, which started at the Delft Gate, or East Gate, crossed the moat by a draw bridge, ran between the sea and the Pettah and ended at Kayman's Gate, where a Portuguese gate used to be. From there the road led along the Kelani River to Hanwella. There were nine bastions: Leiden, Delft and Hoorn on the landside, Den Briel and Amsterdam on the Westside, and Rotterdam, Middleburg, Kloppenburg and Enkhuizen on the southern side. On the west side, on a promontory to the north, were two batteries: the Battenberg battery and the Waterpas battery. On the north side, protected by the batteries, was the harbour, which was not much more than an open road, as there was no bay here. Due to the monsoons the harbour was safe only from December to April. The other eight months of the year the ships had to go to Trincomalee and Galle. On the east side, the land between the moat and the Pettah could be flooded by opening the sluice of the lake, which is now called Beira Lake, possibly from 'de Beer', which was the name of the sluice. The Colombo Fort was a walled city, with administrative and military buildings, as well as cinnamon storehouses, mills, a parade ground, a church, residential buildings, and stalls for horses and elephants. The streets were planted with rows of trees for shade. The houses both inside the fort and in the Pettah were based on the standardised ground floor plans that had evolved from the houses in Holland but had been adapted to the tropical climate to provide shade and ventilation. They had an extended roof covering a veranda to keep the windows in shade, widely spaced masonry columns, a door with a tall decorated fanlight, a high-ceilinged hall with doors leading to the bedrooms, and a living area leading to a back veranda and a paved courtyard with trees, enclosed by wings projecting from the house. The houses were usually one storey high, and had white-washed walls and red-tiled roofs that usually suffered much from the attentions of crows and monkeys. In 1694 some 400 families were living in Colombo, with an average number of 8 persons per family, which included slaves, who accounted for slightly more than half of the population. Of the remaining half, 54 percent were Europeans. Many men were married to Singhalese or mixed Portuguese women. In the 18th century this population group had increased to several thousands. There were families that had lived on the island for five generations. After the British took over many of them stayed on to work as civil servants for the British colonial administration. They eventually forgot the Dutch language and adopted English, but were, and are, still known as the Dutch Burghers. They had Dutch names and often quite distinct European features. They often had money, and occupied high positions in society as lawyers, doctors and academics, and kept apart from the 'common folk'. Their upper class lifestyle and 'outsider ness' caused a certain resentment among the Singhalese, and after the British left most of the Burghers emigrated to Australia, the US and Canada as a result of the 'Sinhala only' policy of the post-independence government during the 1950's and 60's. Michael Ondaatje describes the life of the Burghers in his autobiographical 'Running in the Family' (1983), and Sri Lankan journalist Carl Mueller writes about the 'poor cousins' of the Burghers in his trilogy The Jam Fruit Tree (1993), Yakada Yaka (1994), and Once upon a Tender Time. During the 18th and 19th centuries Colombo became a melting pot of cultures. The Pettah had expanded eastward and southward for several miles and contained a multitude of commercial enterprises of all sorts. An Englishman writes in 1803: 'Colombo is, for its size, one of the most populous places in India. There is no part in the world where so many languages are spoken, or which contains such a mixture of nations, manners and religions'. And as another Englishman writes in 1859: 'The bulk of the Sinhalese (in Colombo) are often handicraftsmen and servants, the Parses are merchants, the Moors retail dealers, the Malays soldiers and valets, the Tamils labourers and coolies, and the Caffre excavators and pioneers. The majority of the Portuguese descendants consist of impoverished artisans and domestics. .... The Dutch Burghers are largely engaged in mercantile pursuits and they fill places of trust in every administrative establishment....By them the whole machinery of government is put into action under the orders of the civil officers.' The British themselves started to take up residence in the cinnamon gardens and the village of Kolpetty on the seaside, on the other side of the lake. Colombo was a good place to live, if one could adapt to the humidity and the mosquitoes. Around 1870 the walls of the Fort were demolished by workers with hammers and pickaxes. The defences were no longer needed and just stood in the way of industrial development. Economic development in the Fort area led to further urban restructuring in which most of the original Dutch buildings were demolished and replaced by 19th century style department stores and offices, causing Colombo Fort to adopt its present British colonial outlook. Today Colombo is a reasonably pleasant city. Compared to most Asian capitals it is a small town where things move slowly and quietly. Only during the rush hours do the thoroughfares turn into noisy, smelly, traffic-congested places of horror. On Sundays everything is dead quiet. Apart from a few neighbourhoods with villas and tree lined lanes in the central area of the city, where the well-to-do live, the urban environment is mostly ugly and dull. Nobody cares enough about what the city looks like to spend energy on its appearance. In the evenings people go walking along the seaside on Galle Face Green that in the Dutch time was a swamp but is now a lawn and a gathering place. It is not green at all but brown, because the grass does not survive the summer heat and the salty air. The dark waves slosh against the small beach and the sea breeze ruffles the women's skirts. The cinnamon gardens that surrounded Colombo in the Dutch period had already gone back to wilderness during the British time. Without the monopoly the cinnamon did not survive competition with the low quality, but cheaper substitutes from South India. British officials built their villas in the gardens close to the Fort, and today 'Cinnamon Gardens' is the name of a fashionable Colombo neighbourhood, with a natural attraction to the modern equivalent of the colonial administrators: the diplomats and development workers with their 'extended families' of servants. Only in the summer months does it get hot, and the lack of rainfall causes water shortages and electrical power failures. The weather is warm and humid most of the year. . In the rainy season there is a tropical shower every day at five o'clock, and the surf on the west coast becomes wild and treacherous. In Colombo sometimes the streets in the lower lying areas get flooded. Because of the terrorist threat from the LTTE there are roadblocks everywhere in the city, but the mood is relaxed. There is no anxiety, though when there is a sudden noise in the distance people speculate it's a bomb explosion. Drive to the east for twenty minutes and you find yourself among low wooded hills and paddy fields. It's quiet and sometimes you see a man-size lizard sunbathing on the road. The cinnamon plantations are all gone. There aren't even any cinnamon trees. On the way to Kandy you pass rubber plantations, and higher up you enter tea country. Every hill is covered with neat rows of tea plants till where it gets too steep and the trees were left standing, like cattle on a high place during a flood. The most important street in Colombo is Galle Road, which at peak hours is full of nightmarish traffic jams. It's not only a Colombo street though. It runs from Fort along the ocean all the way down to Galle. It passes Mount Lavinia, a small seaside resort, and then the industrial area of Moratuwa, and then Panadura, where the busy traffic gradually thins out. Beyond the big dagoba of Kalutara the landscape becomes more rural and the road lonelier. Large stretches of empty beach are to be seen on the right. At Bentota and Beruwala there are big hotels for the foreign tourists, and further south, Hikkaduwa is the backpacker place. Fifteen minutes beyond Hikkaduwa, and some three hours after leaving Colombo, you pass the dark battlements of Galle, after which the road takes a left turn and continues along the south coast towards Matara and Tangalle.

|